Sometimes it is easy to forget that the production and release of music, films and books are driven by the supposed tastes of the masses. After all, you can put on your iPod in the morning on the way to work instead of listening to commercial radio, contribute to Kickstarter campaigns to fund small film and music projects, and track down with increasing frequency (and in respectful restorations) the most obscure of old movie titles. In the case of books, smaller and more specialized publishers often take the chance on works that are considered not mainstream enough by large publishers. And yet, we still see multiple biographies and documentaries produced about many of the same people. This doesn’t necessarily bother me, as again I can navigate towards other tastes. However, it can be hard to find really good treatments of the people that I (and I believe many others) would like to see.

Sometimes it is easy to forget that the production and release of music, films and books are driven by the supposed tastes of the masses. After all, you can put on your iPod in the morning on the way to work instead of listening to commercial radio, contribute to Kickstarter campaigns to fund small film and music projects, and track down with increasing frequency (and in respectful restorations) the most obscure of old movie titles. In the case of books, smaller and more specialized publishers often take the chance on works that are considered not mainstream enough by large publishers. And yet, we still see multiple biographies and documentaries produced about many of the same people. This doesn’t necessarily bother me, as again I can navigate towards other tastes. However, it can be hard to find really good treatments of the people that I (and I believe many others) would like to see.

Author Charles Tranberg is up to the challenge. He has previously written six books: biographies of Agnes Moorehead, Marie Wilson, Fred MacMurray, and Robert Taylor, as well as considerations of The Thin Man films starring William Powell and Myrna Loy and the Disney studios from 1955-1980. In his seventh and latest book, Fredric March: A Consummate Actor, Charles shines a light on the achievements of this actor who, unlike a Bogart or Wayne, was not a personality actor and has had trouble surviving “the test of time” in the public memory. I’m sure glad he did. Tranberg’s work in general, and his latest subject in particular, demonstrate a couple of pertinent things. First, that an author can find a champion for such works, with the supportive and astute BearManor Media publishing Charles’ entire bibliography. Second, that in the hands of an author like Tranberg, there is an outlet for an actor such as Fredric March and a career that is just dying to be remembered.

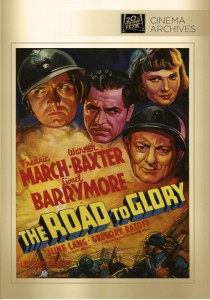

There are ample reasons to remember March: his Academy-award winning roles in Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1931) and The Best Years of Our Lives (1946), Tony Cavendish in that parody on the Barrymores, The Royal Family of Broadway (1930), ‘Death’ in Death Takes a Holiday (1934), Jean Valjean in Les Misérables (1935), Norman Maine in A Star is Born (1937), and the man himself in The Adventures of Mark Twain (1944). He worked with the iconic actresses of the early days of Hollywood sound films, in elaborate costume dramas, sophisticated comedies, and later turns in Executive Suite, Middle of the Night, Inherit the Wind, and Seven Days in May. He was in equal measure screen and stage star, winning two Tony awards for Years Ago and Long Day’s Journey into Night, and often appearing in both with his wife, Florence Eldridge.

As a researcher, I especially appreciated the detailed exploration of Fredric March and his career in this new book. I had a chance to speak with Charles about his latest work, how he approaches writing, and the consummate actor that was Mr. March.

Adam: Why Fredric March?

Charles: Well, for one thing he was born in Wisconsin and two of my prior subjects had Wisconsin ties as well—Fred MacMurray and Agnes Moorehead. Another reason was because March has some of his papers readily available at the Wisconsin State Historical Society in Madison, where I live, so it was easy for me to go and do research. The papers of several of his theatrical producers and many of the plays he appeared in also are at the State Historical Society. These are great resources and I used a lot of the information I got from these papers in the book. Finally, and perhaps the main reason, is because I thought March has become a somewhat forgotten figure and is rarely counted among the classic stars of that era when they are discussed. The truth is that he was one of the most important film stars of the 30’s and an important star on both stage and screen thereafter. I like to select subjects who have not had a ton of books already written about. For instance, I did the first full-length biography of Agnes Moorehead, the first book on Fred MacMurray and Marie Wilson. There is a previous biography of March but that was several years in the past, and it’s very good, but I also include a lot of information about March that isn’t in that book.

Adam: What is your approach to research and writing? Do you spend a lot of time researching and then attempt to write linearly, for example, or do you write chunks of text as you research a particular area?

Charles: I do write as I’m going along. For instance, I will do a lot of research about March and the play “The Skin of Our Teeth” including reading biographies of Tallulah Bankhead, Thornton Wilder, Elia Kazan and going through the papers of the producer of that play, Michael Myerberg as well as any information there is in the March papers regarding the play. I’ll then, once I’m satisfied that I’ve researched that subject well begin writing about it—at least a first draft—and then incorporating it into the book. I thought this play and events surrounding it were so interesting that I devoted an entire chapter of the book to it.

Adam: You’ve become a rather prolific writer on classic Hollywood since your first book in 2005, and have now written seven books. Readers might be surprised to find that you’re not a full-time writer. I also engage with projects outside of my psychology career and am interested in how you think this influences your writing.

Charles: It makes it rather difficult at times. Many times I’m very tired after working all day that I would rather do something other than write or research, and sometimes I do. But I have to force myself to devote a certain portion of the week and weekend to do it. Sometimes it is very easy to do so because it is such an interesting subject. But at other times you have to make time for friends, family, recreation and other projects as well. It can be a difficult balancing act. I wish I would win the lottery and could devote my full time to writing. It is what I love doing most of all.

Adam: You try to provide a balanced portrait of a subject in your books. For example, one anecdote you relate is of the long and happily-married Freddie having a roving eye (or, indeed, hand) on the sets of his films with Claudette Colbert.

I think that writing a considered analysis of a public person’s personality and life is a difficult task. Borrowing from psychology, I think that people’s perceptions of public figures particularly suffer from the fundamental attribution error or the actor-observer effect: mainly, that we stress dispositions or traits for these people’s behaviours and underplay the significance of situations. For example, an actor who is less than cordial to a fan or has a difficult relationship with a co-star is a “bad” person; while, if we were less than friendly, we can think of a dozen reasons (“I was running late” or “I had received some bad news”).

When you come across information about a subject that may cast them in a negative light, how do you handle it?

Charles: I always attempt to be fair and balanced towards my subjects. Everybody I’ve written about I found myself liking or at least admiring their body of work. If you find something that may be a bit negative you can’t suppress it but you have to try and understand it and hopefully seek the reason for some of their actions. March was basically an admirable guy. I truly think he loved his wife and children. He was a great actor who made time for family life and also for good causes, but apparently he had this roving eye and sometimes hands or as Colbert called him “Twenty-fingers Freddie.” The fact is that when she confronted him about his behaviour he should have backed off and respected her, but he really didn’t. His wife and many of his friends thought he had very much a childlike love of life and outlook and sense of humour—in some ways it could be childish. Now on the other hand, some of his female co-stars called him the best husband in Hollywood and said he was devoted to Florence (Eldridge, his wife)—and that he never came on to them. Well maybe they weren’t his type. But truly the stories that Colbert and Evelyn Keyes told about him are disturbing. Despite my liking for him it is my duty as a biographer to write about such things as well as balance it out with those who say he just flirted a bit but never went over the line.

Adam: Which performances do you consider Fredric March’s best?

Charles: I think his performance as Norman Maine in the original A Star Is Born is one of his best and one of the best performances any actor has given. He was really the focus of that film and he played this alcoholic actor on the skids who truly loves the woman truthfully and from what he observed from friends such as Jack Barrymore. The wonderful sequel with Judy Garland makes the woman the main focus where it really should be the man, as good as James Mason is in the sequel he pales in comparison to March’s Maine. His big break with Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde is a tour-de-force, but he is also aided immeasurably in that film by Rouben Mamoulian’s direction, Karl Struss’s photography and Miriam Hopkins’ performance. The Best Years of Our Lives is probably the one film he made that is the best remembered to film fans to this day (the only one of his films to make the AFI list of the 100 Greatest Films). He hasn’t got the biggest role in the film (Dana Andrews does) but he makes all his scenes count especially the ones he shares with Myrna Loy. He gives a deeply poignant performance as ‘Death’ in Death Takes a Holiday.

What might shock some is that he was a wonderful light comedy actor in films like Nothing Sacred, Laughter and I Married a Witch. There are lesser known films in which he shines as well: The Eagle and the Hawk (agonizing over the killing that results from war), One Foot in Heaven (a lovely piece of Americana), The Adventures of Mark Twain and an interesting film about euthanasia An Act of Murder. I also like him in Inherit the Wind with Spencer Tracy, but do think director Stanley Kramer lets him ham it up a bit too much at times.

One performance which may have been his very best, we can only go from contemporary accounts about and that was his work as James Tyrone in the original Broadway production of Long Day’s Journey into Night. I wish he had done the 1962 movie with Katharine Hepburn.

Adam: Looking at his work, Fredric started in early Paramount films and was often second fiddle to a number of dynamic actresses before his success with The Royal Family of Broadway and Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, and then a string of important and successful film and theatre projects. Success was not always guaranteed, however, and there were flops and career setbacks. Most notable were accusations of Communist sympathies that affected his career in the early ‘50s. Through it all, he seemed to work constantly and, perhaps, exhaustingly. How would you describe March’s approach to his career?

Charles: I think he viewed himself as a working actor—never a star. I also think he saw himself more as the years went by as less a leading man and more a character actor—a leading character actor. His craft was what was important and developing a real believable character. That may be one of the reasons why he is not as recalled today because unlike contemporaries like Gary Cooper, James Stewart or Cary Grant—who are fondly and frequently recalled—March never developed a strong screen persona that he carried from film to film that audiences could identify with. As a working actor he worked. When film roles dried up, perhaps due to accusations of being soft on Communism, he worked on the stage. He went into television, one of the first major stars to appear in that medium. I should also note that March was one of the actors who when accused of being soft on Communism or even a Communist he fought back and even won a retraction from one of the rags that made the accusations.

Adam: For some of your other books you were able to interview co-stars, family, friends and others. With Fredric March, being born 1897 and having passed some 40 years ago, this involved mainly co-stars from his later years. Did this influence your research and writing process?

Charles: Well, it makes it more difficult and will continue to be more difficult as the years go by and more people die off. Luckily with March I did have many recollections from people who worked with him who have died off from published and unpublished sources, but more importantly I was able to use wonderful sources including his own papers and papers of those who worked with him to help fill in the holes. Many of those materials never utilized before.

Adam: I feel that anything I ever write influences me. What did you take away from writing a biography of Fredric March?

Charles: For me, March and most of my other subjects grew up in relatively modest circumstances in small towns in the heartland of America (March, Robert Taylor, Fred MacMurray—and to a certain extent, though she was born in the East but grew up in the heartland—Agnes Moorehead), and through incredible will, luck, tenacity and talent transcended their beginnings and in doing so never really forgot their roots. I think that says a great deal about them as people.

Fredric March: A Consummate Actor is available from Amazon, Barnes and Noble, and The Book Depository. Information on Charles Tranberg’s other books can be found on his Amazon author page. He also has a Facebook page.